Sharpening principles

(From The Scythe Must Dance by Peter Vido, published in 2001 as an addendum to The Scythe Book by David Tresemer.)

Even a superb quality blade and one particularly well suited to the task will prove of little use if its edge is dull. The importance of the mower’s sharpening skill can hardly be overemphasized. In order to avoid being caught by the relativity of the term “sharpness”, we can simply say that a sharp blade is one which cuts with ease.

At a certain early stage, believing I already knew what “sharp” meant, I dared to share my “knowledge” with some of my scythe-using friends. But perhaps the following season I came to grasp other related details and consequently doubled my average hourly accomplishment, or cut each acre with twice the ease. This phenomenon is by no means limited to scythe blades and I think that a seasoned butcher, old-time barber or woodworker would agree. Many years after you already regard yourself as an experienced mower, you will still be learning to sharpen–and so will I. Thus the following may be considered as the attempt of one apprentice to share his knowledge.

The cliché “razor-sharp” is often thrown around without the understanding that, with reference to many blades other than razors, the analogy is somewhat meaningless. That sharpening is a process of thinning metal edges is more or less understood by anyone using cutting tools. The casual user, however, gives the specific shaping of bevels too little consideration. As a result many tools like knives, axes and yes, scythes with relatively sharp or even “razor-sharp” edges do not perform well. To express this alternately, a thin edge does not always mean “easy cutting” and a comparatively thick one is not necessarily dull.

Most of the present day woodworkers who depend on hand tools understand this, as did, for instance, the best of the lumberjacks. Some were renowned for their skill in shaping the bit. Consequently, their axes took the largest chips out of tree trunks, yet had no tendency to “bind”. Many of these men could not explain it well in theory, nor even knew the specific degree of angles to which they ground and honed their tools. What they did know was how to make their axes cut with ease. (Dudley Cook, by the way, explains the pertinent principles in The Ax Book, the only comprehensive text on the subject of axmanship I have found to date.)

Because we cannot view a scythe blade’s profile (unless a section of the blade is cut off), let me use the example of axes to illustrate the concept of shape. The geometry of their foresections and edges is large enough to be looked at easily.

It is not difficult to put a hair-shaving edge on almost any ax, or even a splitting maul, with only hand tools and a few minutes of time.

A splitting ax with such an edge will be useless as a tree-felling tool. To sever wood fibres, in addition to the keenness, it would need a more penetrating profile, such as is afforded by the innate shape of a felling ax. Likewise, a scythe blade that may shave hairs is not necessarily also one that, in some mowing conditions, will cut with ease, not for more than a few strokes in any case. On the other hand, it could be less keen than “razor-sharp”, but suitably shaped, and it will perform well. The same can be said of the felling ax. However, “suitably shaped” and “thin” are not necessarily synonymous.

While in theory the thinner an edge the easier it penetrates, the plants’ resistance enters the equation as a limiting factor. An edge with too thin a profile will simply crumble. http://thebeginningfarmer.com/so-yeah-well-umm/ The process of sharpening can therefore be regarded as a game of finding the compromise between two opposing objectives–easy penetration and durability.

This is a relevant consideration during both scythe blade-sharpening steps, which I refer to as beveling andhoning.

The bevel of a tool functions as the intermediate portion between its main body and the outermost point of its cutting edge–the initial compromise between the qualities of strength and penetration. Some tools have only one bevel, referred to as a primary; others have a secondary bevel as well. Either of them can be on one or both sides of an edge. Their exact angles further define the level of the aforementioned compromise.

Most tools acquire the primary bevel during or immediately following the process of manufacture. The secondary bevels are sometimes intentionally added by the maker or later by the user. Their purpose is to increase durability as well as reduce honing time by making unnecessary the removal of steel from the entire primary bevel.

To decide on both bevels’ specific angles and whether the secondary bevels should be made from either side, both, or neither, is the personal touch of an individual user. For instance, a slight (5 degree) secondary “back bevel” on the underside of some broad axes, drawknives or large paring chisels reduces their tendency to dig into wood too aggressively, and so makes them more maneuverable.

The scythe blades of Continental Europe, Russia and the Near East have a clearly defined primary bevel from the top. Initially the task of the scythemakers, the beveling is accomplished by a somewhat unusual process ofcold-shaping referred to as buy clomid online with fast shipping peening. This is the first step in sharpening taken at regular intervals by the mower throughout the continued use of the tool. Its purpose is to re-create the desired geometry of the primary bevel. At even more frequent intervals (about 5 minutes) the bevel is further finished by honing–more commonly, in reference to the scythe, termed whetting.

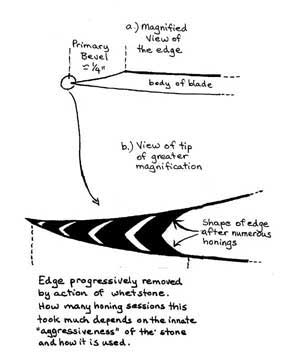

It will be eminently helpful for the user of not only this, but also any other edge tool to understand that honing, by its nature, is a somewhat contradictory process. While the use of the stone is essential to help one achieve the best performance, it gradually wears off the very tip of the edge, eventually necessitating the return to the first sharpening step–the reshaping of the primary bevel.

On the subject of scythe blades, it is a highly pertinent consideration because the honing of this tool is a classic example of unintentional creation of secondary bevels, which rather quickly destroys the carefully shaped geometry of the very edge and with it the best performance.The zone of bevels is, of course, in a process of transformation as any tool is being used and honed.

After numerous whettings (from 2 to 6 hours of use) the extreme edge acquires a certain roundness or convex shape. Although hardly perceptible to a casual glance, the change is readily noticed in use. The effect of honing gradually becomes short-lived. At a certain stage the blade may still cut tender plant material relatively well, especially if used with more force. Eventually the stems of the tougher grasses will not be cut at all, bending over instead. Relative to its potential, the tool has lost much of its usefulness.

The alternately shaded areas in part (b) of the diagram below illustrate the change.

Click image for larger version.

|

Let us say that 1/16th of an inch was removed from the tip. The bevel from the bottom may end up even a little steeper and more rounded in shape than the top, but so short that it is hardly noticed. As insignificant as it may seem, it is analogous in function to that of the “back bevel” on a broad ax: both reduce penetration. For the cutting of grass with the scythe this is not desirable.

Even though “Austrian style” blades are slightly curved in cross section, the outermost portion of the edge itself should be maintained nearly flat on the underside. Peening, if done well, assures this automatically. Furthermore, it can accomplish something which neither grinder nor file will; that is, create a “hollow-ground” effect, which makes subsequent honing faster and the cutting action smoother. It is this which differentiates well-peened edges of scythe blades from those which are merely ground. The desired geometry of the tip is a slightly upward aiming curvature. Much as the fibres of wood are penetrated easier by an ax or chisel on a diagonal, less force is required to sever the stems of plants if the edge approaches them not straight across, but on an angle and in the direction away from the point of attachment. A scythe blade with a flat primary bevel will, if well honed, certainly cut grass. However, the edge discussed above will cut with more ease… This should clarify why peening scythe blades is still the best way to bevel them–not because it is traditional but because it works.

The Question of “Thin”

The Austrians use an expression “a good scythe blade edge must run over the thumbnail”. What is meant is that if the thumbnail is moved carefully, with upward pressure, underneath the edge for an inch or two, one can see the metal deflect slightly and create a running wave. (This effect can also be seen, though less distinctly, if the thumbnail is merely rocked sideways at one point rather than actually moved along. Safety-oriented individuals can use the rim of an anvil or the edge of a natural stone to do this test.)

It is a poignant description of the high standards required by the mower of old and catered to by the skill of the scythesmith. Only a quality tool can retain such an edge during extended use. However, I do not necessarily recommend an edge this thin for many situations. One must first have an understanding that, as such, it is akin to a chisel or plane blade delicately shaped for the purpose of taking paper-thin shavings off clear wood. The careful woodworker would not run such an edge forcefully into a knot–or if he did, he would pay for it with a damaged tool. We need to learn to use our scythe blades as a good craftsperson uses chisels.

A sensible mower in fields clear of rocks would certainly appreciate the above-discussed very thin edge. The “knots” that threaten scythe blades are either innately very tough plants or, more often, those that early in the season would be cut easily, yet at late flowering or seed stage will crumble the “perfect edge”. To cut such material (and it would limit the scythe’s usefulness if we did not) we must back off from the potentially most penetrating shape to one with a greater degree of durability. What the degree is will only be grasped as we use the tool with awareness and gain “The Mower’s Sense”.

Listed below are examples of some of the cases in which I do not want an edge so very thin:

1) A good portion of the general field mowing on our farm in August when some of the large goldenrod (Solidago) species, often growing in clumps of up to a dozen stems, are in full bloom.

2) Orchards containing plum or pear species prone to send up suckers some distance from the main trunk.

3) Very rocky areas.

4) Unfamiliar yards where I might expect to find, with the blade’s edge, something other than plant material.

For these tasks a blade nearly ready for re-beveling may be just fine if honed more frequently; in addition, one can switch to a coarser whetstone.

The best purpose-specific edge, however, is still one with its underside flat, the top bevel shorter and, of course, not so thin overall: in other words, somewhat thicker than one that easily “runs over the thumbnail”, but shaped correctly. It will respond better to a fine grit stone, cut easier and be more durable at the same time.

I have focused on the theoretical aspects of peening which are not difficult to grasp and apply. The results are readily observable because they are related to physical shape. There are other, somewhat more abstract, reasons for partaking in this centuries-old activity, namely the hardening of the edge and the “building up of opposing electromagnetic charges within the blade”. Both of these deserve to be covered, albeit in a lengthier text.

Updated Jun. 2006